Why Emotional First Aid Should Start With Your Body – Not Your Brain

Six years of therapy. Countless insights, conversations, and cognitive tools under my belt. And still – there I was again, frozen in front of my laptop, unable to decide which folder to open next. Three days until the deadline. Five tabs open. Ten tasks running through my head. I clicked one document, then another, then just stared at the screen, wondering what I was even doing. Everything felt like too much.

No thought helped. No clever mindset trick. Even though I understood exactly what was going on – I was simply exhausted. My brain shouted, “Pull yourself together!” but my body had already hit panic mode.

The turning point came much later at a seminar. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard about bottom-up processing (I’d been talking about emotions for years), but for the first time, I actually experienced it in my body.

Emotions live in the body

We live in a world that runs on performance. Head on. Gut off. We override ourselves because the project needs to get done. Because everyone else keeps going too. Because that’s what we’ve learned. And then we’re surprised when a single sentence in a meeting knocks us off track. Or when a simple decision (Send the email? Eat lunch?) sends us into a spiral.

What often gets overlooked: Emotions don’t just happen in the mind. They emerge in the interplay between body and brain.

According to neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett, what we call “emotion” is a constructed experience – shaped by physical sensations, context, and past learning. Your brain constantly scans your internal state (heartbeat, breath, muscle tone) and tries to make sense of what it finds. That process is called interoception (Quadt et al., 2018).

And because your system is wired for survival – not comfort – it prioritizes safety over well-being. Which means: when your body senses stress, your perception narrows. You become more sensitive, less flexible. Cognitive strategies stop working.

Bottom-Up: The body before the brain

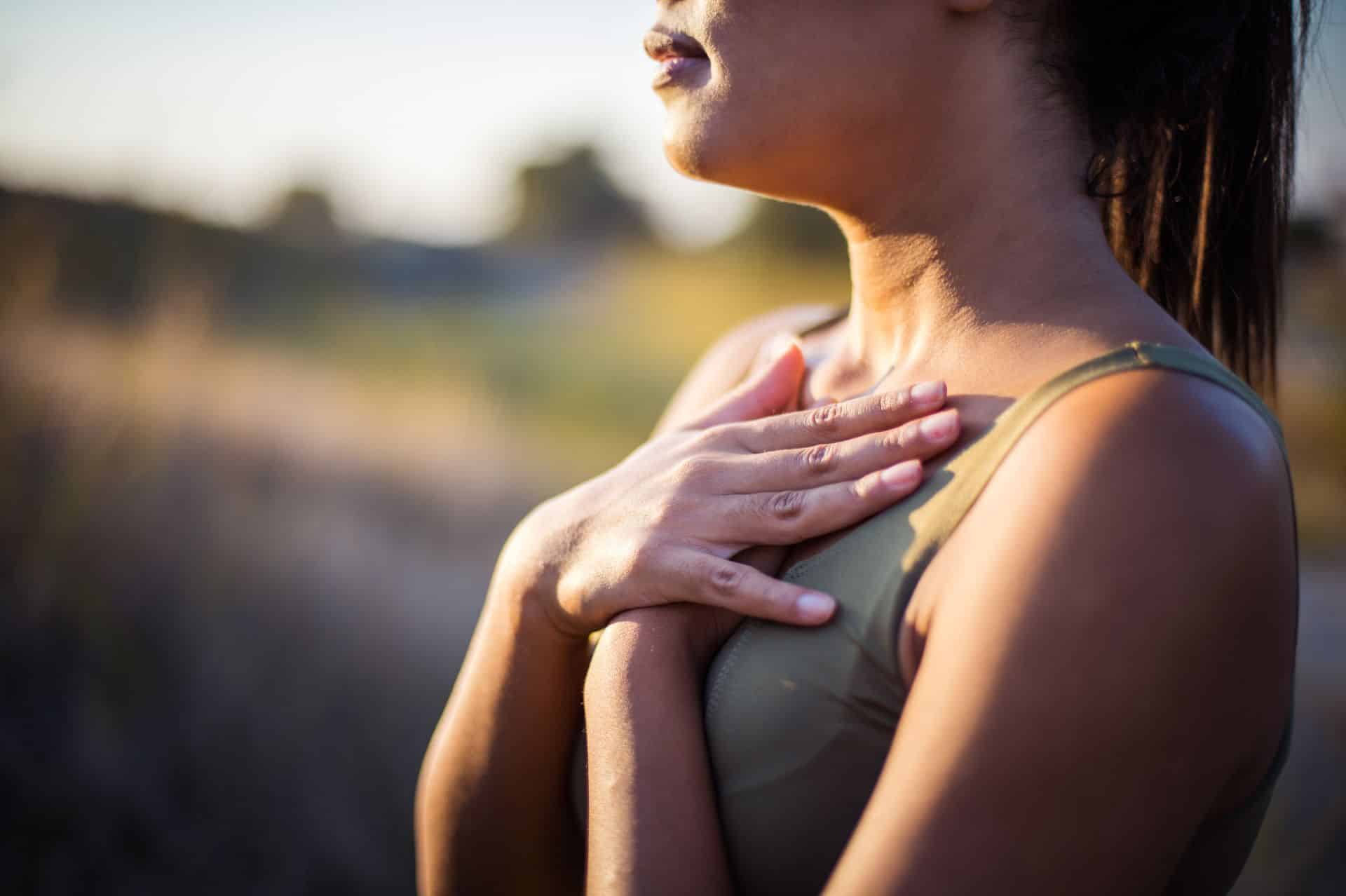

Emotional self-support doesn’t start with affirmations or mindset hacks. It starts by noticing what’s happening inside your body.

When you feel overwhelmed, don’t ask “Why am I like this?” Ask: “Where do I feel this – and what might my body need right now?”

Maybe it’s a break.

Maybe it’s food.

A quiet place.

Maybe it’s shaking things out, stretching, or five minutes of just lying on the floor.

These small moments of self-regulation are often the real turning point. No drama. No deep breakthroughs. Just a soft internal “Hey, I’m here.”

Emotional strength is physical

We often think emotional resilience means having it all together. Staying cool. Pushing through no matter what. But real strength looks different. It starts with recognizing when your system is overloaded and choosing not to push through, but to slow down.

Instead of forcing yourself to stay “rational,” you learn to stay present in your body. Because when your nervous system sounds the alarm, even your sharpest thoughts won’t land. Your brain is in survival mode, and there’s no room for clarity or creativity there.

Resilience isn’t about how well you can explain your emotions. It’s about how well you can feel them. How early you notice: “Something’s tightening. I feel off.” And how gently you respond:

Not with analysis.

But with a breath.

A pause.

A moment that brings you back into your body – so your mind can catch up.

Final thought: Start with safety – and start low

Emotional regulation isn’t a mental bootcamp. It’s a body-based practice. Your system doesn’t want logic first. It wants safety.

So next time you feel overwhelmed, don’t try to think your way out. Try to feel your way back in. Because sometimes, the wisest answer isn’t found in thinking. It’s found in sensing.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Price, C. J., Hooven, C., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Interoceptive awareness skills for emotion regulation: Theory and approach of mindful awareness in body-oriented therapy (MABT). Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00798

Quadt, L., Garfinkel, S. N., & Critchley, H. D. (2018). Interoception and emotion: Shared mechanisms and clinical implications. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084934

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.